Asterisk: Inline styles with the power of CSS. A bad idea?

What if you could style any HTML element entirely within your markup without any external stylesheets or inline styles — using real CSS syntax, complete with pseudo-selectors and media queries?

That’s the idea behind my attribute-driven styling approach called Asterisk.

✨ Use any CSS property as a HTML attribute. ✨

Introduction

Confession: I use inline styles and don’t feel bad about it. I know they’re considered bad practice for reasons x, y, z — I know. I care deeply about accessibility and performance for production sites and apps.

But that doesn’t mean that the same technology can’t be used for something different: rapid prototyping.

Sometimes all I want is to try out an idea. How would this look with a hover effect? What if I change the focus style? What if we made this text larger? How would this look with a background blur?

Inline styles are often the fastest way to apply arbitrary styles to an element. No class, no abstraction, no jumping to a different file or line of code, no build process, no opinionated language to learn. But also no styliing of hover states, no media queries, no pseudo-elements.

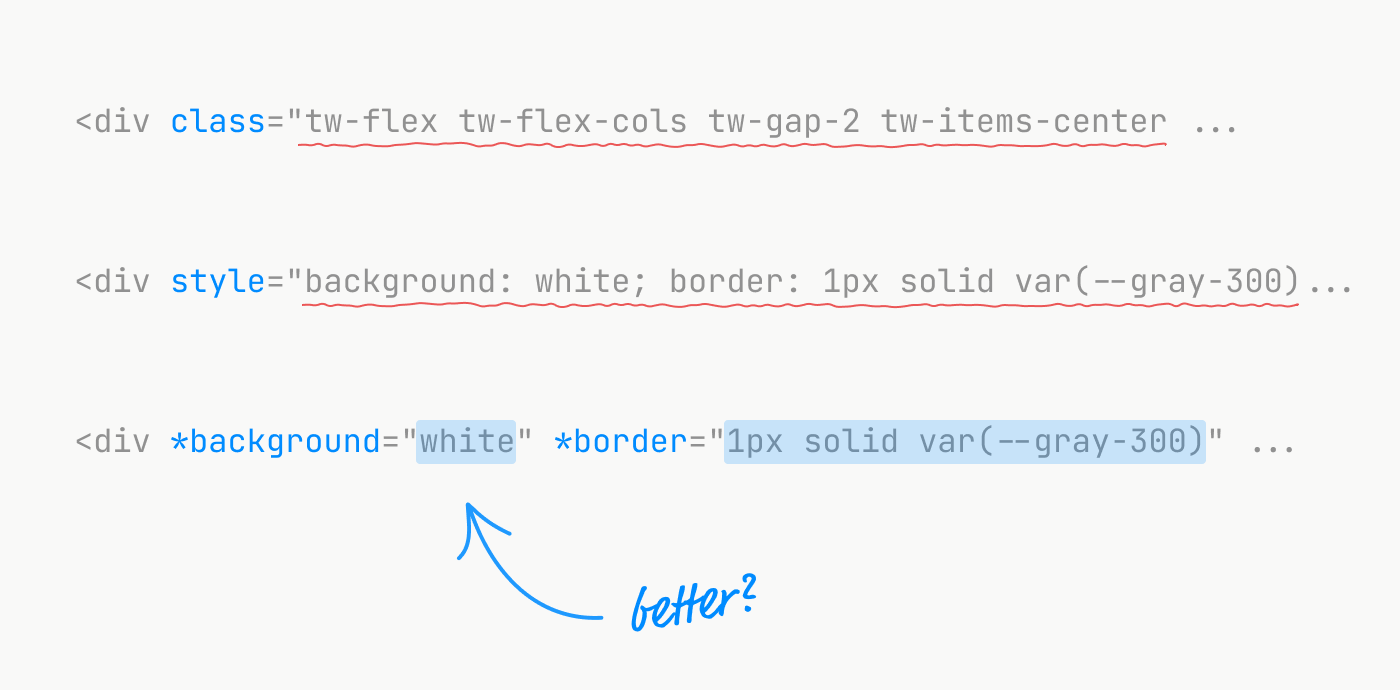

Apart from those limitations — which are already a dealbreaker — I don’t like that all CSS properties and values are stuffed into a single style attribute. I also don’t like it when lots of Tailwind class names are stuffed into a single class attribute.

It’s fast to write but messy to look at later.

The design tool vs. code gap

There’s a fundamental difference in how designers and developers work with visual properties.

In creative tools like Figma, Pitch, or Framer you select a layer and style it directly.

Want to change the background? Select the layer, pick a color. Want to adjust padding? Select it, modify the value. You might use shared styles or design tokens for consistency, but most properties are changed on that specific thing you’re looking at. It’s immediate. It’s direct.

With HTML and CSS, the default is abstraction.

You can’t just “style the div and change it on hover.” You first need to create a class name or ID, then write CSS somewhere else that targets that abstraction.

This creates friction. Not just for designers learning to code, but for anyone who thinks visually and wants to iterate quickly.

My friction with Tailwind CSS

One might ask: Why don’t you use Tailwind? It’s direct, it provides the abstractions out of the box! Well, I do use Tailwind at work daily. But even after years of using it, I still only know a small subset of utility classes, mostly for layout purposes. That’s all I need to compose React components.

Here’s how most of my prototype code at work looks with a custom Tailwind prefix:

<div class="tw-flex tw-flex-cols tw-gap-2 tw-items-center tw-overflow-auto tw-h-full tw-border">

<!-- React components that others made -->

</div>Tailwind works brilliantly for common styling needs that follow a rigid system of standard component libraries, but falls apart when you want to push the boundaries and break the rules:

<div class="grid grid-cols-[1fr_500px_2fr]">

<!-- ... -->

</div>Or from the Tailwind docs:

<div class="bg-[#bada55] text-[22px] before:content-['Festivus']">

<!-- ... -->

</div>While Tailwind offers arbitrary styles, and you can solve almost every use case somehow, it feels like a crutch. I can use it, but I don’t like it.

In the past 20 years, I’ve worked so much with CSS that I know it by heart.

Learning Tailwind means unlearning CSS in favor of learning a new set of class names.

That might be okay for developers who don’t know CSS well, but it’s not a good use of time for someone who knows a large portion of the CSS dictionary already.

I’d much rather write inline styles and know exactly what I need to write and what the result will look like.

If only …

The problem with inline styles

Unfortunately, inline styles have gotchas, even for prototyping: no support for @media queries, no support for pseudo-selectors like :hover, no way to use ::before or ::after.

<div style="

background: white;

border: 1px solid var(--gray-300);

border-radius: var(--large);

box-shadow: 0 2px 5px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.1);

">These are readable, familiar, and direct. But limited.

But: For interactive and responsive states, we must reach for CSS classes.

CSS classes require us to form abstractions, come up with names, and usually define CSS in a different file. That breaks flow and adds friction:

<!-- index.html -->

<div class="card"></div>/* styles.css */

.card {

background: white;

border: 1px solid var(--gray-300);

border-radius: var(--large);

box-shadow: 0 2px 5px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.1);

}

.card:hover {

transform: scale(1.1);

}That’s what Tailwind solves. Instead of coming up with class names and wiring things up, I can stay in the HTML. No indirection. But at the cost of setting up a build system, installing dependencies, learning new syntax and vocabulary. And at the cost of readability.

Writing Tailwind is fun and fast. Reading it is difficult:

<div class="bg-white border border-gray-300 rounded-lg shadow-sm hover:scale-110 transform transition-transform duration-200">

<!-- Card content -->

</div>The best of both worlds?

Is there a way to have the developer experience of Tailwind, but without the burden of another vocabulary to learn?

Can we use CSS itself as the language, keep everything in the markup, and still support pseudo-selectors and media queries?

Can we bring the directness of design tools to code?

What if…

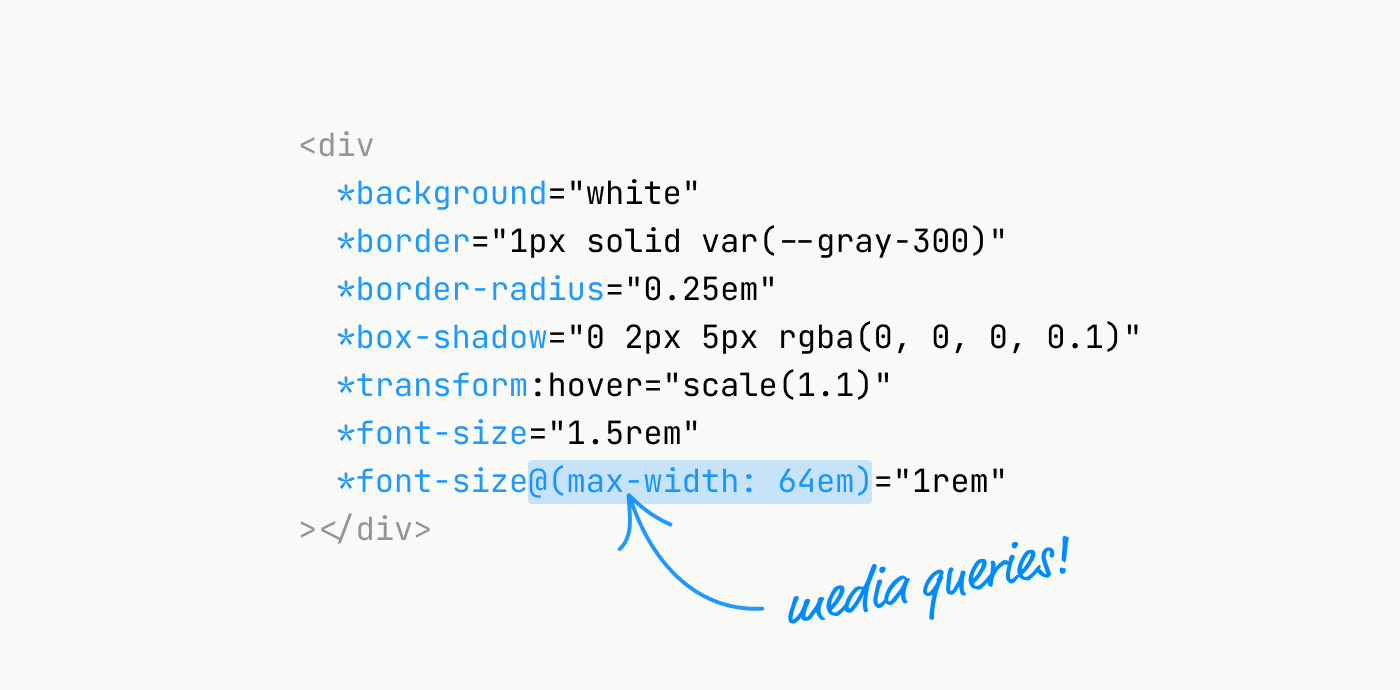

Instead of writing CSS in a stylesheet, we define styling directly in markup using attributes that start with an asterisk (*):

<div data-theme="dark">

<div

*color="var(--brand)"

*font-size="200px"

*background="var(--surface-1)"

*padding="4rem"

*color:hover="red"

*cursor="pointer"

>

Hello

</div>

</div>✨ We can use any CSS property as a HTML attribute. ✨

Each *property="value" attribute is automatically converted into a real CSS rule at runtime. The element declares its own style behavior — without losing CSS flexibility.

CSS-on-demand

The magic happens in a small JavaScript runtime that scans the DOM, extracts all * attributes, and builds valid CSS rules dynamically.

Each rule is stored in a Map, keyed by a combination of property, media query, pseudo-selector, and value. This makes deduplication trivial and keeps the generated stylesheet efficient.

When attributes change, a MutationObserver detects it and regenerates only what’s needed. The system stays reactive without requiring a framework.

Syntax

Here’s how the attribute naming works:

<!-- Basic CSS property -->

*color="red"

<!-- Adds pseudo-selector -->

*opacity:hover="0.5"

<!-- Scoped to media query -->

*font-size@(max-width: 600px)="16px"

<!-- Uses CSS custom properties -->

*background="var(--surface-1)"Generated output

For the example above, the runtime emits CSS like:

[*color="red"] {

color: red;

}

[*opacity:hover="0.5"]:hover {

opacity: 0.5;

}

@media(max-width: 600px) {

[*font-size="16px"] {

font-size: 16px;

}

}

[*background] {

background: var(--surface-1);

}Why?

This system isn’t meant to replace traditional CSS for large-scale web sites and apps. It’s incomplete. But it’s simple and fast, ideal for prototyping.

Direct, declarative, portable

Styles live next to the elements they affect.

Framework-agnostic

Works with plain HTML, React, Web Components.

Custom property aware

Integrates seamlessly with design tokens.

Supports pseudo-classes and media queries

Handles real-world styling scenarios.

Zero CSS files

Ideal for quick prototypes or dynamic UIs.

Readable and familiar

Uses actual CSS properties, not abstracted class names.

LLM-friendly

Large language models know CSS, so they are fluent with Asterisk, too.

Why the * (asterisk)?

I knew I couldn’t just use raw CSS property names as HTML attributes. Some CSS properties already exist as (deprecated) HTML attributes: bgcolor, background, height, to name a few.

There’s another constraint: the HTML specification requires custom attributes to contain a dash (-). But I really hate typing dashes for quick prototypes. So I thought: what if I prepend something that looks cool instead? I settled on the asterisk (*).

Technically, it’s not spec-compliant, but I doubt HTML will ever introduce *-prefixed attributes as a standard.

And with custom elements becoming more common, the dash requirement feels… somewhat obsolete anyway. Besides, this is for prototypes.

I don’t really care about strict compliance here.

Funny enough, I later discovered that Angular uses *-attributes (like *ngIf) as signals to their template compiler. So this isn’t an entirely new or exotic idea.

Implementation

Here are 120 lines of JavaScript to make it work:

What’s missing?

While a lot can be done, many CSS features can’t be used: child selectors, keyframe animations, etc. – but it would be possible and only a matter of deciding on the syntax. But again: This is not meant to be a full replacement for CSS anyway. It’s an addition for certain use cases.

Conclusion

By extending attribute syntax to cover CSS behavior, we get the best of both worlds: semantic markup and full styling flexibility. Without touching a stylesheet.

It’s not about replacing CSS or Tailwind for production apps. It’s about removing friction during the creative process. When you’re exploring ideas, every extra step like opening another file, naming a class, configuring a build tool pulls you out of the flow.

Asterisk keeps you in the markup, using the CSS you already know, with the power of pseudo-selectors and media queries at your fingertips.

If you feel adventurous and like to experiment, drop the script into your page and start adding * attributes or try the demo on CodePen

I don’t think I will use Asterisk to style everything. But with its tiny runtime, it might come in handy as a default drop-in script for my future prototypes and CodePens.

And since the syntax is almost identical to CSS, LLMs can easily understand and generate code.

Finally: if you really would want to take this to production, a build-time script could easily discover used attributes and extract them to a static stylesheet.

But let’s not even go there. Happy prototyping. 🕹️

Continue reading:

-

Tidy text: Sloppy notes that auto-correct, one line at a time

-

Design engineering 101: Typeahead like Spotlight and Omnibox

If you like this article or have feedback, follow me on Mastodon.